“There can be no happiness if the things we believe in are different from the things we do,” said British explorer Freya Stark. In 1927, aged 33, while the majority of her contemporaries were embedded in domesticity, she embarked on her first expedition. Boarding a ship to Beirut, her destination was the places she’d encountered through the pages of her favourite childhood book, One Thousand and One Nights.

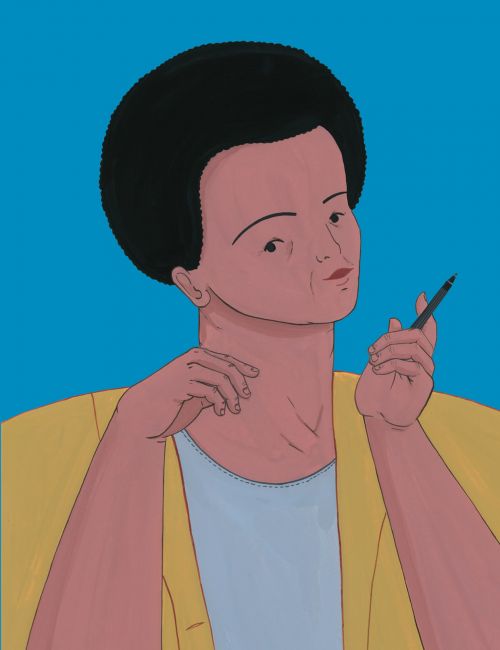

Explorer Freya Stark, illustrated by Viktorija Semjonova for Oh Comely issue 31.

While Stark’s travels in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and Persia in the 1920s and ‘30s did benefit cartographers by filling in hitherto blank maps, greater still was their effect on a transfixed audience back home. Over her 25 books, she transported readers to the far-flung corners of the atlas, bringing it to life with the characters of the people she encountered, descriptions of how they dressed, ate, lived, and imparting her own giddy delight in exploration.

Stark’s first book, The Valley of the Assassins, published in 1934, charted her journey in an area barely visited by Westerners, let alone Western women. She travelled alone and unarmed, as she did on all her travels. Over time, her packing evolved to include letters of introduction, medication, small gifts to hand out, as well as copies of Jane Austen and Virgil. Clad in Dior dresses and favouring elaborate hats to hide the effects of a disfiguring childhood accident, Stark took advantage of her gender to experience the aspects of women’s lives hidden from her male counterparts and, when she wanted, to bend the rules. “The great and almost only comfort about being a woman is that one can always pretend to be more stupid than one is and no one is surprised.” Her desire for exploration wasn’t driven by conquest or a need to assert superiority, but by curiosity, “I travelled single-mindedly for fun,” she stated.

In her 1939 Baghdad Sketches, where a medical emergency left her close to death, she recounted that, “It was not my sins that I regretted at that time; but rather the many things undone”. Living until she was 100, and travelling into her eighties, Freya Stark was a woman who would never be “done”.Further reading: One Thousand and One Nights (Penguin Classics); The Valley of Assassins by Freya Stark (Modern Library Inc); Baghdad Sketches, Freya Stark (IB Taurus and Co Ltd)

This feature originally appeared in Oh Comely issue 31.