Roger Ebert was perhaps the most prominent American film critic of all time, known not just for the 46 years he spent writing reviews for the Chicago Sun-Times but also for his popular and enduring television programme At the Movies. After complications from cancer treatment necessitated the removal of his lower jaw, Roger spent the final years of his life unable to eat or speak, and yet his writing diversified and flourished during this time. In Steve James' absorbing new documentary Life Itself, based on Roger's memoir, the film-maker explores his extraordinary story while filming him during what turned out to be the last few months of his life.

Ahead of its release in cinemas, Steve sat down with us to talk about the film's complicated road to production.

When you're making a documentary about a man who co-hosted a television show for decades, published scores of books and reviewed almost every film that came out over nearly half a century, where do you start in your research?

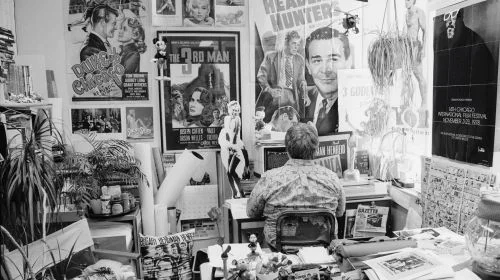

The memoir itself was the template. It was an incredible bible for the film, and inspired in so many ways. It helped to organise his life and tell me what was important to him, which guided me towards who to interview. He devotes chapters to significant film-makers like Martin Scorsese and Werner Herzog but also Bill Nack, his friend from college, and John McCue, his newspaper buddy. That said, he doesn't really talk about his film criticism in the book. He excerpts some of his profile writing, but not a single review. He doesn't talk about his show much either – there's just a simple chapter devoted to it. So there were things that I wanted to do more on and in that regard it also led me to other sources. There was a lot to get my arms around.

In addition to being a prolific writer, Roger also had a storied life. How did you decide how best to weigh your coverage of it?

After I read the memoir I knew I wanted as much as reasonably possible for the film to be a comprehensive biography of Roger's life, taking account of his critical place in cinema, his impact and what he contributed, as well as his remarkable personal life and journey. I wanted it all, but we weren't going to make a three-hour film or a mini-series, either of which we could have easily done. Instead, I wanted it to be no longer than two hours and as comprehensive as it could be in that time. That meant picking and choosing. There were lots of things we could have dealt with that we didn't, but I feel good about the choices we made. I think we hit most of the significant milestones in his life, but hopefully not in a scattershot way.

One of the most affecting things about Life Itself is how you show Roger handling the prospect of death with dignity and grace. Was that important for you to capture?

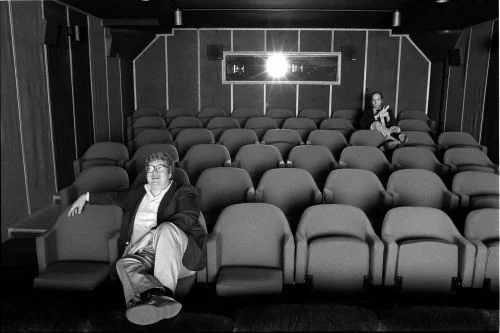

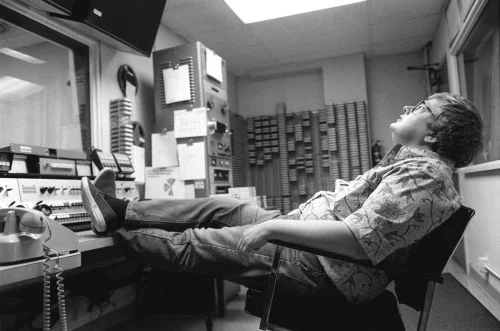

Absolutely. When we started the film we had no idea that he would pass away four months in. That just wasn't in our thinking. His health was more unstable than it had been and he was growing increasingly fragile, but he was otherwise fine. The memoir is written from the perspective of someone late in life who has been through a lot and is reflecting, so I loved the idea of going back and forth between the present and the past and finding interesting ways to do that. I wanted to film Roger going to the cinema, writing, travelling, seeing friends – even though he could no longer speak he'd still throw dinner parties and sit at the head of the table. I was going to show what a vigorous life he continued to live despite all he'd been through, and in that we would get some sense of his perseverance, his courage, his good humour in the face of everything. All of that is in the movie, it's just we didn't get to film it. We ended up shooting him largely in a hospital and a rehab institute, but those earlier things became far more poignant because you know that he is dying.

There's a moment in the documentary where Roger writes that it would be a major lapse if you didn't depict the full reality of what he was going through, but was there anything you were personally worried about showing on film?

I was initially concerned when I first got to the hospital. If you look at any pictures of Roger in public after the start of his health problems he was either wearing a black turtleneck or a white scarf wrapped around his neck. He was always very stylish, but it was strategic as well. When I walked into the hospital room for the first day of actual filming he was asleep and his jaw was hanging down. There was nothing there. It was quite pronounced and I remember thinking, “I don't know how people are going to handle this.” But I filmed it, he woke up, smiled, and his eyes lit up. I put that early in the movie to let people see what he was going through and allow them to feel that inevitable discomfort. My hope was that they'd have the same experience I had where it stops being shocking – you see past the illness and see him. You're looking into his eyes, not down his throat. For a man who was dying, he made this easy. He was remarkably co-operative and engaged.

Memoirs are usually adapted for the screen as fictionalised accounts rather than as documentaries. What did you think a documentary could express about Roger's life that might have eluded a scripted feature?

Biopics are particularly hard to do because there's a tendency to want to tell everything, and trying to tell too much can work against the inherent drama of the storytelling. It can feel like a connect-the-dots presentation of a person's life – you're never in one place long enough to feel the deep significance of that moment in their life. You have the same potential hindrance in a documentary, but one of the advantages if the subject's alive is you have them there in flesh and blood, so who they are is communicated as much by their presence as by their important milestones. For example, if we were making the scripted biography of Roger's life, we probably wouldn't spend as much time as we did on his daily travails and him coping with his condition. You're not going to give up screen-time to illness when you could be showing him when he adapted Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, hanging out with Russ Meyer and big breasted women. But in a documentary you can get so much from observing simple moments in someone's life: the way they answer a question, or how they look at their wife.You see how they live.

Life Itself is out in UK cinemas today.