After three decades of directing actresses including Cate Blanchett and Julianne Moore in their defining roles, Todd Haynes finds himself amazed by deaf 14-year-old Millicent Simmonds

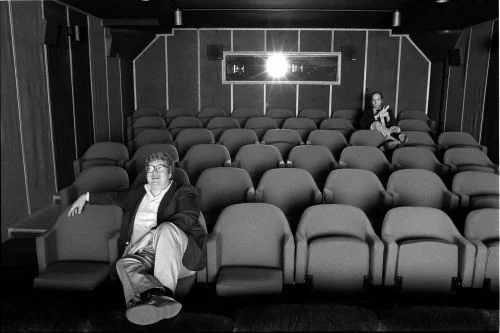

Portrait of Todd by Ellie Smith

Todd Haynes has been living in the past for some time. Each of his films – from Velvet Goldmine to I'm Not There to the sublime Carol – has been set in earlier periods and made using cinematic techniques from those eras. His most recent film Wonderstruck splits its time between pasts, telling an intertwined story of two deaf children in the 1920s and 1970s as they each run away from home and experience New York's frenzied enchantment.

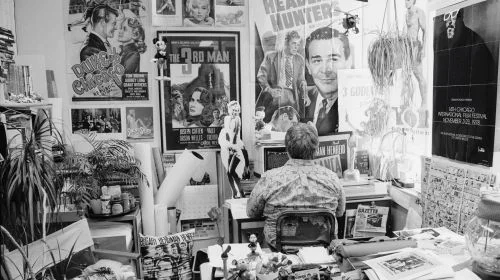

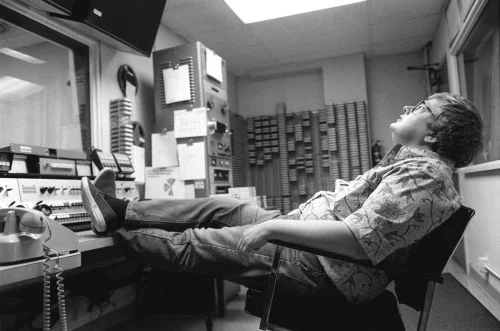

Wonderstruck nods towards silent movies and 1970s American cinema. Are you interested in capturing something about how the world was at certain points, or is it more what older films tell us? It varies. Speaking through the prism of film language is sometimes exclusively, almost academically what I'm trying to do: Far From Heaven was set in the late 1950s and was about what those films said about their own time through the artificial language of Technicolor melodramas. Wonderstruck is a little different in that I was thinking about the kids' subjectivity. I felt a messiness in the 1970s. You see images of children from that time and their hair is in their face! Particularly there was a sense of the tactile in their creative interests. I think of Wonderstruck as what they're making with their hands. It feels handmade in that way, and going back and forth between the stories it's almost like pieces of a puzzle being pressed together by little dirty fingers. My films are always interpretations of cultural themes, stories, characters, real people, cinema. I never feel like I'm inventing new ideas, nor is that my intention – I'm just commenting on the culture as it exists and recombining components. I'm curating my films, maybe, much like these kids explore the idea of museum curating.

Is there a kinship between the job of film director and museum curator? You both locate different things, put them together and find the relationships between them. Absolutely. You're not just curating themes and references and in my case historical moments – selecting what is relevant from your research and films and popular culture – you're also putting together creative partnerships. Actors, cinematographers, costume designers, all of those elements are selected yet also have an autonomy. You may guide them but ultimately as a director you're letting something out of your control happen, and that's also the thing you want to capture, to let it in.

Until now you've collaborated mostly with adults, but much of the film is on the shoulders of Millicent Simmonds, a deaf 14-year-old. Did that affect how you worked? Every actor is different anyway. They bring their own personality, temperament, and in the case of professionals, their own training and approach to their work. The cliché that directing is really about casting is true: it's selecting that right person and providing them with confidence so they can take risks and do things that neither of you knew were possible. I know I have good instincts and I'm surrounded by people whose opinions I trust, but I've also been very lucky. With Millie there were unknowns on top of unknowns, but we followed our instincts and met this extraordinary kid. She has an understanding of the camera and the medium that you can't teach, that you can't direct out of anybody. I'm not sure how she knows just the right amount of information to express, or even what she looks like when she's performing. How many of us really know what we look like as we talk and emote? And she's a kid! It's a weird thing. Julianne Moore, who has that same understanding of the scale of the medium, would look at Millie on set and say wow, there's something remarkable here.

There are few deaf characters in cinema, let alone stories about deaf people. Do you feel that in losing dialogue you also gain something in those complications of communication? It asks the audience, who will mostly be hearing viewers, to supplement information, to imagine what it's like to be without hearing but also to interpret things in ways they're not usually asked to. When I was 12, The Miracle Worker became a point of obsession for me. I know it was about Helen Keller as a phenomenon but it made me think about language. Initially she represents a rejection of social norms and law and language, a wilful postponing of entering the codes and terms of a society. That's fascinating when you're young. I think kids feel an affinity for deafness and blindness, for limits and novel ways of improvising how to communicate and express yourself. Limited abilities and freedoms and constraints are built into their status – they get it.

Wonderstruck is in UK cinemas 6 April 2018